GEOLOGICAL ORIGINS OF THE BAROLO WINEGROWING AREA

By Edmondo Bonelli, naturalist

The Barolo wine growing area extends over a substratum composed of sedimentary rock, which was formed over a relatively short period of time corresponding to the late Miocene epoch. Yet despite this common thread running through the overall formation, considerable differences in terms of both process and composition are to be found in the continuous succession of ancient marl, sand and sandstone, more recent marl, chalk and marsh deposits.

A large part of Lower Piedmont used to be occupied by the Ligurian-Piedmontese Tertiary Basin, an extensive depression engulfed by the sea and surrounded by the arc of the Alps and the Ligurian Apennines, which were both in course of being formed. The sediment eroded from the surrounding areas was gradually accumulating on the seabed, burying the older strata: an uninterrupted sequence of deposits that tells the story of more than six million years of history associated with the colossal movements that led to the build-up of the Alpine edifice.

The most ancient origins of the Langhe date back to around 30 million years, during the lower Oligocene. The first deposits are to be found in the south east (Ceva, Millesimo, Cairo Montenotte), forty kilometres from the Barolo growing area: salt marsh sediments represent the entry of the sea into the narrow valleys of the early Alps, with fossil evidence of remote, warm and damp forests to be seen in the strata rich in coal which were exploited in the past through mining. Above them – and also highly fossiliferous – lie the first real marine sediments. Initially, the depth of the sea was limited, generating shallow tropical environments, with a warm, clear sea which allowed for the development of coral reefs that are still perfectly preserved today. In the past, these strata – called the Molar Formation – welcomed stretches of vineyards growing the dolcetto varietal, as they still do in the Ovada area.

Approximately 25 million years ago the depth suddenly increased due to the subsidence of the entire area associated with the genesis of the Alps. The basin was transformed into a large strait, which in certain points was as much as over 600 metres deep (1968 ft). And so it remained until 12 million years ago, when the deposits of strong beds of sandstone mixed with layers of marl formed what are today the Upper and Asti Langa, a vast area where the moscato bianco varietal has been grown extensively since time immemorial, and the Alta Langa DOCG designation was introduced more recently for a brut sparkling wine made from a blend of pinot noir and chardonnay.

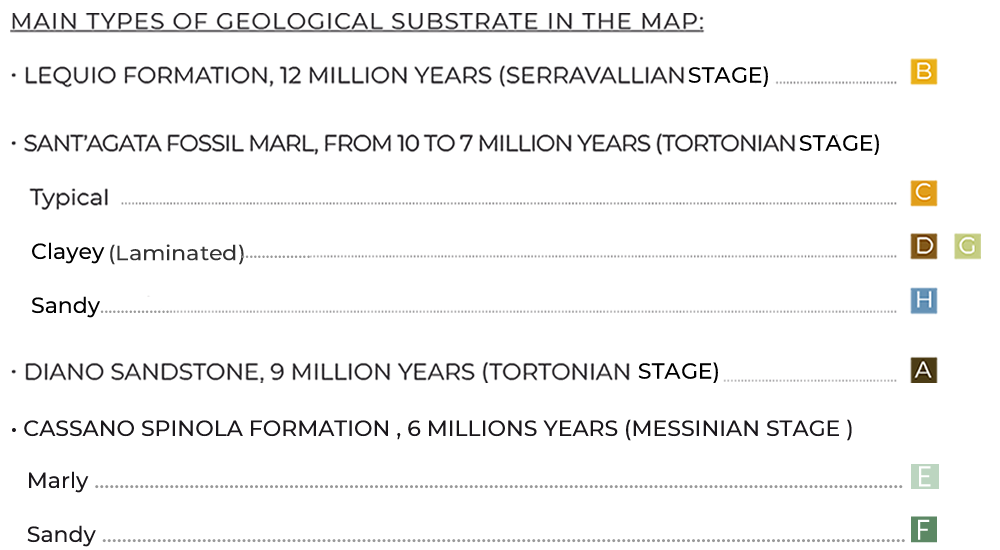

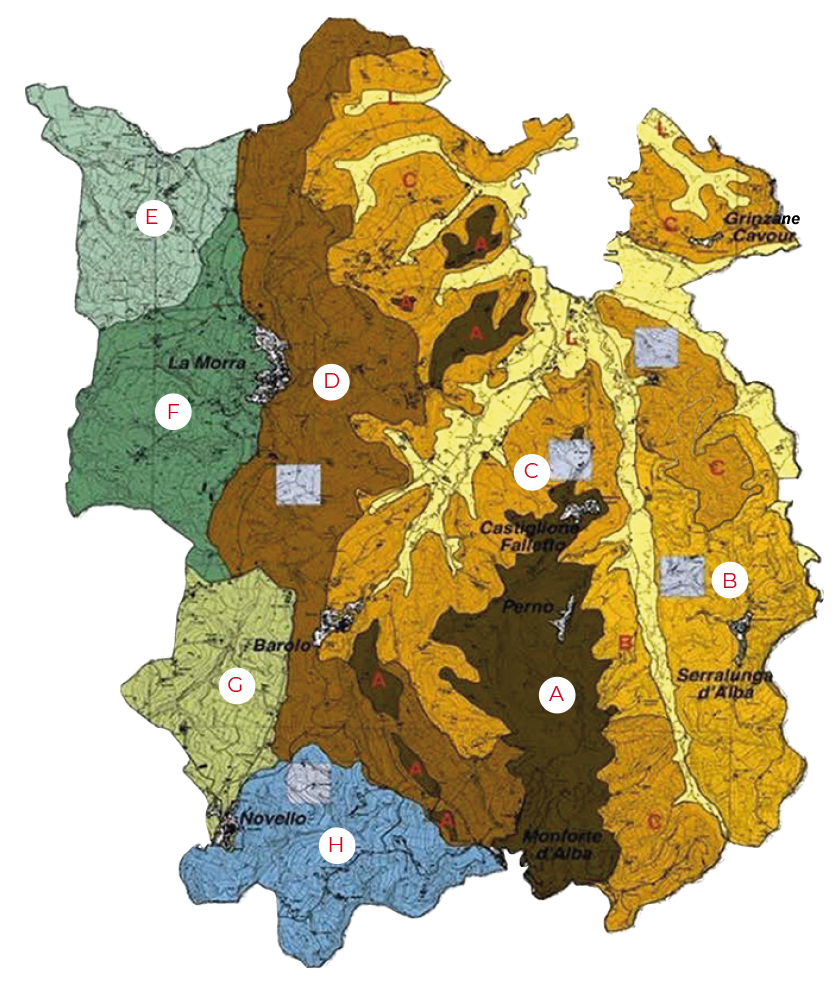

Retracing the history of the ancient Piedmontese sea, we come to the stage at which the rocks that today make up the Barolo winegrowing area were formed.

The oldest section, which retains some of the particular features of the deposits of the Upper Langa, is called the Lequio Formation. It forms the substratum of the hill of Serralunga and a part of Monforte, and is marked by the alternation of strata of compact, light-coloured marl with layers of at times well-cemented sand which results in the typical local Langa stone.

Often these strata are well-cemented, and their resistance to erosion has meant that parts of this formation have been preserved at the top of the highest hills surrounding Monforte. Diano Sandstone was formed following major submarine landslides, which transported sandy sediments to the beds from the coast.

Stretching out over more than half of the area above the sandstone is Sant’Agata Fossil Marl. This comprises mainly fine, silty and clayey sediments which represent a phase of “tranquil” settlement, when there were no strong submarine currents. Some variability is to be found, with areas rich in thin strata of sand and others with mainly silty layers.

Around 6.5 million years ago the marl sedimentation was unsettled by one of the most substantial geological phenomena of all time, when crustal movements slowly led to the closure of the Strait of Gibraltar. The Mediterranean basin remained isolated, and it was inevitably subject to intense evaporation, leading to its almost total desiccation. During this catastrophic event, extensive beds of gypsum crystals were deposited, and today they can be seen on the western slopes of the hill of La Morra-Verduno, testifying to the disappearance of the Mediterranean and its inhabitants for a long period of time. Those deposits are known as the Formation of the Vein of Gypsum, and they appear in a band running throughout the rest of Italy as far as Sicily. Where before there was sea, saline lagoons in which the gypsum settled began to be formed, followed by saltwater marshes similar to the present-day Maremma in Tuscany. Muddy sediments, sand and pebbles transported by rivers accumulated in this marshy ground to create the formation of Cassano Spinola.

We have reached 5.4 million years ago, and have arrived at the north-eastern border of the Barolo wine area.

Map source:

“La zonazione del Barolo, Soster e Cellino, Regione Piemonte, 2002”